-

Whatsapp: +86 13526572721

-

Email: info@zydiamondtools.com

-

Address: AUX Industrial Park, Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, China

-

Whatsapp: +86 13526572721

-

Email: info@zydiamondtools.com

-

Address: AUX Industrial Park, Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, China

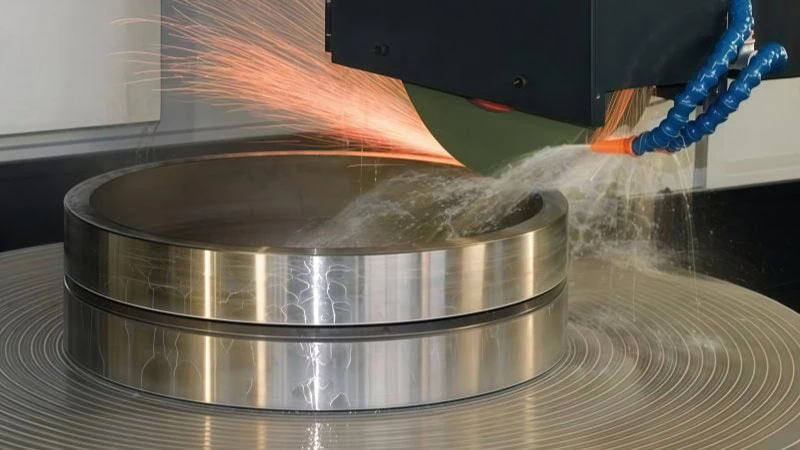

Why You Need Coolant for Surface Grinding: 5 Critical Reasons

Why is the application of coolant considered a non-negotiable requirement for high-precision surface grinding operations?

Coolant is essential for surface grinding because it dissipates the intense heat generated by friction to prevent thermal damage and maintain dimensional accuracy. Additionally, it lubricates the wheel interface to extend tool life, optimizes surface finish by flushing away debris, and ensures operator safety by suppressing hazardous dust.

Preventing Thermal Damage and Metallurgical Defects

Why is effective cooling critical for preventing catastrophic failure during the surface grinding process?

Coolant serves as a vital heat transfer medium that rapidly absorbs and carries away the intense thermal energy generated at the contact point between the grinding wheel and the workpiece. Without this immediate cooling action, the localized temperature at the cut zone would spike uncontrollably, causing irreversible structural damage to the metal and rendering the part unusable.

Dissipating Heat Generation in the Grinding Zone

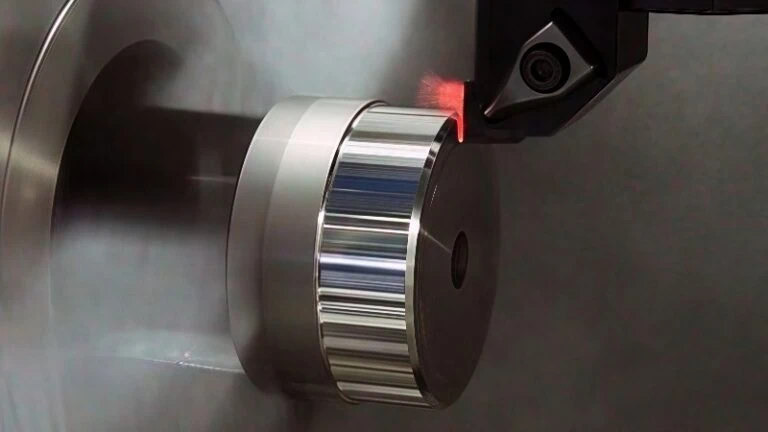

Surface grinding is an aggressive process. Unlike turning or milling, where a single tool edge cuts the metal, a grinding wheel has thousands of tiny abrasive grains. Each grain acts like a microscopic cutting tool. As these grains plow through the material, they generate significant friction.

Consequently, this friction creates an immense amount of heat. In dry grinding scenarios, temperatures in the cutting zone can rapidly exceed 1000°C (1800°F). This is comparable to using a dull drill bit on a hard piece of steel without oil; the tip turns red hot almost instantly due to friction, often ruining both the bit and the hole.

The primary job of the coolant is to flood this interface. It acts as a thermal barrier. The fluid absorbs the heat from the workpiece surface and the abrasive grains, then flushes it away into the machine’s filtration system. By keeping the temperature stable, you prevent the heat from “soaking” into the core of your workpiece.

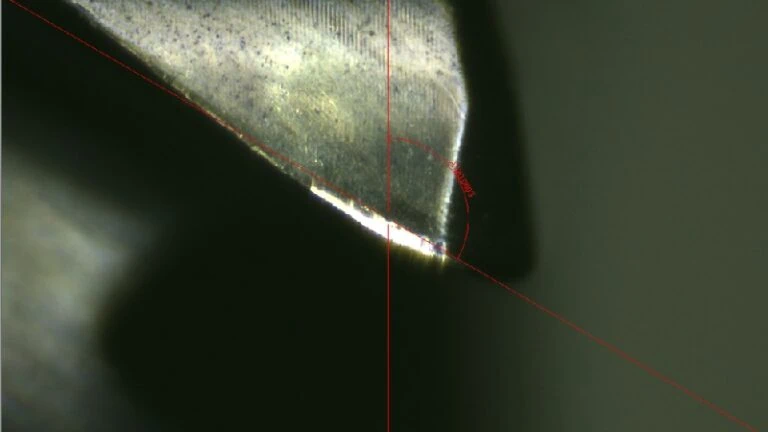

Avoiding Grinding Burn and Surface Cracks

If the heat generated is not removed quickly enough, the surface of the metal will overheat. This phenomenon is commonly known in the industry as “Grinding Burn.”

Grinding burn is not just a cosmetic issue; it is a sign of severe thermal distress. Visually, you might see discoloration on the surface of the part. The metal reacts with oxygen at high temperatures, creating an oxide layer.

Here is a general guide to identifying thermal damage by color:

| Discoloration Color | Severity Level | Potential Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Straw / Light Yellow | Mild | Slight surface oxidation; usually acceptable for roughing. |

| Brown / Bronze | Moderate | Potential hardness loss on the very surface. |

| Blue / Black | Severe | Scrap part. Deep structural damage and likely cracking. |

Furthermore, rapid heating followed by rapid cooling causes thermal shock. When the surface expands from heat but the core remains cool, it creates high tensile stress. Eventually, the metal surface creates tiny spider-web cracks to relieve this stress. In the machining world, this is often called “checking.” These micro-cracks can cause the part to shatter under load later on.

Preserving Workpiece Hardness and Material Integrity

The most dangerous aspect of heat is what you cannot see. Even if the part looks shiny and has no burn marks, it might still be damaged internally. This relates to the metallurgical integrity of the steel.

Most parts sent for surface grinding are already heat-treated to achieve a specific hardness (measured in Rockwell C1, or HRC). However, grinding introduces new heat. If the temperature at the grinding zone exceeds the steel’s original tempering temperature, the metal will undergo “Re-tempering” (or Annealing).

Essentially, the heat makes the steel soft again.

For example, consider a hardened punch die used in manufacturing. If you grind it without sufficient coolant, the surface might soften from 60 HRC down to 45 HRC. When that punch hits the production line, it will wear out or deform almost immediately because it lost its hardened shell.

Conversely, in some alloys, extreme heat followed by the quenching effect of the coolant can make the surface too brittle (creating untempered martensite). This makes the surface prone to peeling or flaking off.

Note: The specific temperature at which steel loses its hardness varies significantly depending on the alloy grade and prior heat treatment. Always check with your material supplier to confirm the critical temperature limits for the specific steel you are grinding.

Ensuring Dimensional Accuracy and Stability

How does uncontrolled heat fundamentally alter the final measurements of your precision ground parts?

Coolant ensures dimensional accuracy by neutralizing thermal expansion, preventing the workpiece from growing during the grind and subsequently shrinking out of tolerance, while also stabilizing machine components to maintain consistent geometry throughout long production cycles.

Counteracting Thermal Expansion in the Workpiece

When metal gets hot, it gets bigger. This is a basic law of physics known as Thermal Expansion2. In surface grinding, friction creates heat, which causes your workpiece to expand specifically in the direction of the cut.

Imagine you are grinding a steel block to a specific thickness. If you grind the part dry, it heats up. While it is hot, you measure it, and it reads exactly 10.000 mm. However, once you take that part off the machine and let it cool down to room temperature, the metal shrinks back to its natural size.

Suddenly, that part measures 9.995 mm. You have now ground the part undersized, and it is likely scrap.

This happens because the grinding wheel removes material based on the expanded size. Coolant prevents this by keeping the workpiece at a stable temperature (ideally 20°C / 68°F) throughout the entire process.

Consider the behavior of standard steel. For every degree of temperature rise, the metal expands a tiny amount. This might seem small, but in precision grinding, it adds up fast.

Table: Impact of Temperature Rise on a 500mm (20 inch) Steel Workpiece

| Temperature Rise | Expansion Amount | Result |

|---|---|---|

| +5°C (9°F) | ~0.03 mm | Minimal error, often acceptable for roughing. |

| +20°C (36°F) | ~0.12 mm | Critical Error. Exceeds most finish tolerances. |

| +50°C (90°F) | ~0.30 mm | Catastrophic dimension loss. |

Stabilizing Machine Component Temperatures

Coolant does not just cool the part; it cools the machine itself. During long operations, heat from the grinding zone transfers into the magnetic chuck and the machine table.

If the machine table heats up unevenly, it can warp or bow. In the CNC milling world, this is similar to “thermal drift,” where the spindle grows in length as it warms up, causing Z-axis errors.

In surface grinding, if the magnetic chuck gets warm, it expands upwards. This brings the workpiece closer to the grinding wheel than the machine controls realize. As a result, the grinder removes more material than programmed.

By flooding the grinding area, coolant acts as a temperature regulator for the entire machine bed. It ensures that the reference plane—the table your part sits on—remains flat and stable.

Holding Tight Tolerances During Long Grinding Cycles

Surface grinding is often the final step in manufacturing. It is used to achieve extremely tight tolerances, often within +/- 0.005 mm (0.0002 inches).

Achieving this precision requires consistency. However, grinding takes time. A large mold plate might require hours of back-and-forth passes.

Without coolant, the process becomes unstable over time.

- Start of shift: The part is cold. The cut is shallow.

- Middle of shift: The part accumulates heat. It expands towards the wheel. The cut becomes deeper, increasing load.

- End of shift: The wheel pushes away (deflects) due to the heavy load, or cuts too deep.

Coolant breaks this cycle of instability. It ensures that the first pass and the final “spark-out” pass happen under the exact same thermal conditions. This allows operators to trust their down-feed settings without constantly stopping to re-measure a hot part.

Maximizing Grinding Wheel Life and Efficiency

Beyond protecting the part, coolant is the primary factor in maintaining the tool itself. It drastically extends grinding wheel life by lubricating the abrasive grains to slow down physical wear and by flushing away metal chips to prevent wheel loading. This preservation of the wheel’s cutting structure reduces the need for frequent dressing operations, thereby maximizing machine uptime and significantly lowering consumable tooling costs.

Lubrication to Reduce Friction at the Wheel Interface

Grinding is often mistaken for a pure cutting action, but it actually involves a significant amount of rubbing. Each abrasive grain on the wheel acts like a tiny plow. Without lubrication, the friction between the grain and the workpiece wears the grain down rapidly.

Coolant acts as a slick barrier between these two surfaces. It reduces the mechanical stress on the abrasive bond posts. This is similar to tapping a threaded hole in steel. If you run a tap dry, the friction dulls the cutting edges instantly, and the tap might snap. If you add tapping oil, the tool glides through, and the cutting edges stay sharp for hundreds of holes.

In the grinding industry, we measure this efficiency using the G-Ratio3 (Grinding Ratio). This is the volume of material removed from the workpiece divided by the volume of wheel lost.

- High G-Ratio: You remove a lot of metal while losing very little wheel.

- Low G-Ratio: Your wheel is crumbling away just to remove a small amount of stock.

Effective lubrication directly improves your G-Ratio. It allows the abrasive grains to fracture cleanly (self-sharpening) rather than dulling prematurely (glazing).

Flushing Swarf to Prevent Wheel Loading

“Loading” occurs when the material you are grinding gets stuck in the empty spaces (pores) of the grinding wheel. This is a common issue when grinding “gummy” materials like soft steel, aluminum, or 304 stainless steel.

Think of using a hand file on a piece of soft aluminum. After a few strokes, the teeth of the file get packed with metal filings. Once that happens, the file no longer cuts; it just slides over the surface.

In surface grinding, a loaded wheel behaves the same way. The sharp grit is buried under packed metal chips (swarf). The wheel loses its bite and starts to rub instead of cut.

High-pressure coolant acts as a power washer for your wheel. It blasts these chips out of the porous structure before they can weld themselves to the abrasive. This keeps the wheel “open” and aggressive. If you do not flush this swarf away, the wheel becomes a solid disc of metal-on-metal friction, which destroys efficiency.

Reducing the Frequency of Wheel Dressing Intervals

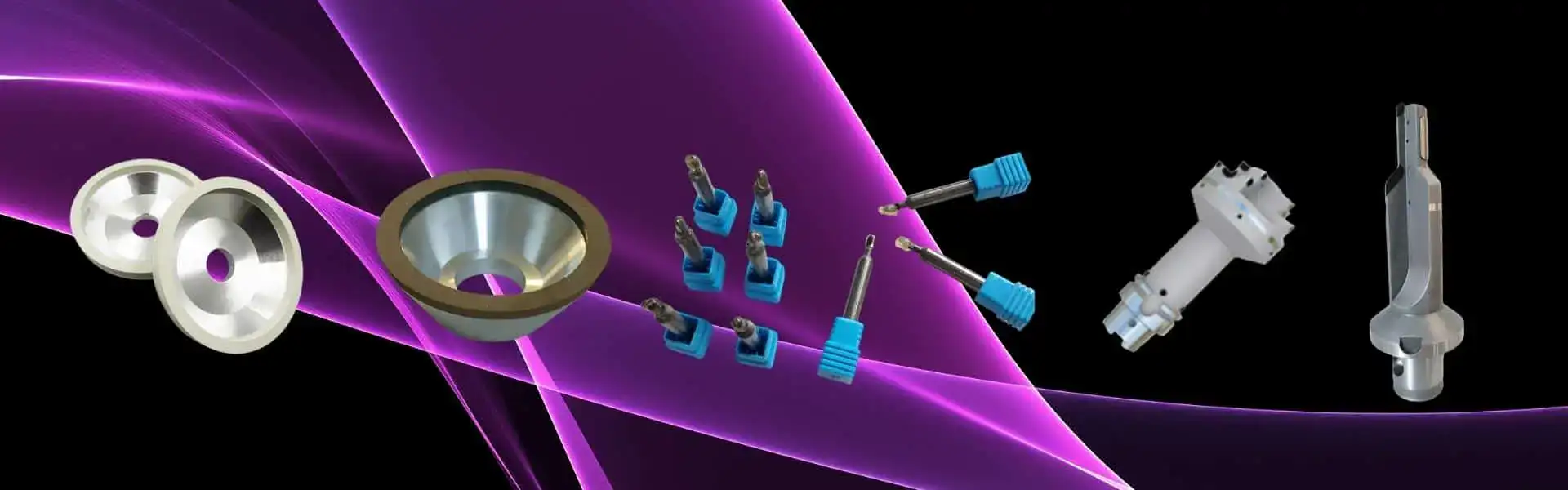

Dressing is the process of using a diamond tool to shave off the outer layer of the grinding wheel. We do this to expose fresh, sharp grit and to restore the wheel’s flatness.

However, dressing4 is a “necessary evil” for two reasons:

- It consumes the wheel: Every time you dress, you are throwing away expensive abrasive material.

- It stops production: The machine cannot grind parts while it is dressing the wheel.

By preventing loading and reducing wear, coolant allows the wheel to cut effectively for much longer periods. This means you do not have to stop and dress the wheel as often.

Table: Estimated Impact of Coolant on Dressing Frequency

| Scenario | Condition of Wheel | Dressing Interval (Example) | Production Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Grinding | Rapid loading; grains glaze over quickly. | Every 5 passes | High Downtime (Stop & Go) |

| With Coolant | Wheel stays open; grains fracture naturally. | Every 20 passes | 4x More Continuous Grinding |

Note: The specific dressing interval depends heavily on the hardness of the wheel bond, the grit size, and the material being ground. Always monitor your spindle load meter; a rising load usually indicates the wheel needs dressing.

Optimizing Surface Finish Quality

When aiming for high-precision aesthetics and function, coolant plays a pivotal role. It optimizes surface finish quality by flushing away loose abrasive grit to prevent random scratches, providing essential lubricity that allows for cleaner cuts with lower roughness averages (Ra), and inhibiting the wheel clogging that generates vibration marks.

Minimizing Scratches from Loose Abrasives and Debris

In surface grinding, “cleanliness” equates to quality. As the grinding wheel breaks down, it sheds used abrasive grains. Additionally, the process creates thousands of tiny metal chips. If these loose particles remain in the cutting zone, they roll between the wheel and the workpiece.

This creates random, deep scratches often called “fishtails” or “comet tails” on the surface.

High-volume coolant acts as a flushing agent. It captures these loose particles immediately and carries them away from the finish surface. However, simply pumping coolant is not enough; the coolant must be clean.

If your coolant tank recycles dirty fluid without proper filtration, you are essentially sandblasting your precision part. For mirror finishes, effective filtration (often down to 10-20 microns) is mandatory.

Table: Recommended Coolant Filtration Levels for Surface Finish

| Desired Finish Quality | Recommended Filtration Size | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Roughing | 50 – 100 Microns | General stock removal |

| Fine Finish (Ground) | 10 – 20 Microns | Bearing races, mold plates |

| Mirror Finish (Polished) | < 5 Microns | Optical surfaces, gauge blocks |

Achieving Smoother Ra Values through Effective Lubricity

Surface roughness is usually measured in Ra (Roughness Average)5. To get a lower Ra number (a smoother surface), the abrasive grain must cut the metal cleanly.

Without lubrication, the grain tends to “plow” through the material rather than cutting it. This plowing action pushes metal aside, creating jagged peaks and valleys on the microscopic level.

Coolant provides the necessary lubricity to reduce this friction. It allows the grain to penetrate and shear the metal chip off smoothly. This is chemically similar to how cutting oil prevents tearing during heavy machining operations.

Generally, neat oil (straight oil) coolants provide better surface finishes than water-soluble coolants because oil has superior lubricity. Water dissipates heat better, but oil makes the surface smoother.

- Water-Soluble Coolant: Great for keeping parts cool, typically achieves Ra 0.4 µm (16 µin).

- Neat Oil Coolant: Superior for lubrication, capable of achieving Ra 0.1 µm (4 µin) or better.

Preventing Chatters Caused by Wheel Clogging

“Chatter” is the enemy of a perfect finish. It appears as distinct, parallel wave marks or a “barber pole” pattern across the workpiece.

While chatter can come from machine vibration, it frequently comes from the wheel itself. When a grinding wheel loads up with metal swarf (as discussed in the previous section), it loses its roundness and balance. The loaded sections rub against the part instead of cutting.

This rubbing causes the wheel to bounce or skip microscopically against the workpiece surface. This vibration prints a wave pattern directly onto the steel.

By using high-pressure coolant directed specifically at the wheel’s face, you prevent this metal build-up. The wheel stays sharp and free-cutting. A free-cutting wheel exerts lower, more consistent cutting forces, which eliminates the self-induced vibration that causes chatter marks.

This is similar to a milling cutter on a CNC machine. If chips weld onto the cutter flutes (known as Built-Up Edge), the cutter becomes unbalanced and hammers the workpiece, leaving a poor finish. Coolant prevents that buildup, ensuring the tool runs smooth and true.

Secondary Benefits for Equipment Protection and Safety

Beyond the immediate grinding process, coolant protects your valuable ecosystem. It serves as a critical protective barrier that prevents flash rust on freshly ground metal surfaces and machine components by depositing a temporary anti-corrosive film. Simultaneously, it actively captures and suppresses airborne dust particles at the source, ensuring a breathable and safe working environment.

Protecting the Machine Bed and Workpiece from Corrosion

When you grind steel, you strip away its outer layer. This exposes “naked” metal that is highly reactive to oxygen in the air. Without protection, this fresh surface reacts almost instantly with humidity. This phenomenon is known in the industry as “Flash Rust.”6

If you use plain water to cool a part, it will likely rust before you even take it off the machine. However, industrial coolants contain chemical rust inhibitors. These additives leave a thin, residual film on the workpiece. This film protects the part during the time gap between the grinding operation and the next stage of production.

Furthermore, coolant protects the surface grinder itself. The magnetic chuck and the machine’s precision guideways (ways) are made of cast iron or steel. They are constantly splashed with fluid. If that fluid lacks rust inhibitors, your expensive machine bed will corrode.

Pitting corrosion on a machine table ruins its flatness. If the table is not flat, you cannot hold tolerance, no matter how skilled the operator is.

Table: Corrosion Protection by Coolant Type

| Coolant Type | Rust Protection Level | Residue Characteristics | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straight Oil | Excellent | Oily film; long-term protection. | Carbide grinding, high-precision steel. |

| Soluble Oil (Emulsion) | Good | Waxy/Oily film; sufficient for in-process. | General purpose grinding. |

| Synthetics | Variable | Tacky or dry film; relies heavily on chemical additives. | Light duty, keep-clean operations. |

Note: The effectiveness of rust inhibitors degrades over time as the coolant ages. Concentration levels (Brix %) must be monitored daily. Consult your coolant supplier for the correct refractometer reading to maintain rust protection for your specific water hardness.

Suppressing Hazardous Grinding Dust for Operator Health

Dry grinding generates a massive amount of fine dust. When an abrasive wheel shatters metal at high RPM, it creates microscopic particles known as particulate matter.

In a dry environment, this dust becomes airborne. It forms a cloud that drifts through the shop. This creates two serious problems:

- Machine Damage: The abrasive dust settles onto the slideways of nearby machines, acting like a lapping compound that wears out moving parts.

- Health Risks: Operators breathe this dust in.

This is particularly dangerous when grinding Tungsten Carbide or exotic alloys. Carbide grinding dust often contains Cobalt, a heavy metal that can cause severe respiratory issues (often called “Hard Metal Lung Disease”) if inhaled over time.

Flood coolant acts as a “scrubber.” It captures the dust exactly where it is generated—at the wheel interface. The liquid encapsulates the fine particles and washes them into the machine’s sump tank before they can float into the air.

Using coolant converts a potential air quality hazard into a manageable liquid sludge, ensuring the shop air remains clean and compliant with safety regulations.

Conclusion

Understanding why you need coolant for surface grinding goes beyond simply cooling a hot part; it is about ensuring the total integrity of the manufacturing process. From preventing the invisible dangers of metallurgical re-tempering to stabilizing microns of thermal expansion, coolant is the silent guardian of precision.

Whether you are aiming for a mirror finish, extending the life of your grinding wheels, or protecting your team from hazardous dust, the correct application of coolant is the defining factor between a scrap part and a quality component. While coolant is critical, it works in tandem with your tooling. Even the best cooling system cannot compensate for a poor-quality wheel. Therefore, ensuring you have the right combination of high-performance abrasives and effective cooling is the true secret to maximizing productivity and part quality.

- Rockwell Hardness Test1 – Wikipedia article explaining the Rockwell Hardness scale and testing method.

- Thermal Expansion2 – Wikipedia entry explaining the physics of how materials expand under heat.

- G-Ratio3 – ScienceDirect topic page defining the Grinding Ratio (G-Ratio) and its use in measuring wheel efficiency.

- Dressing4 – ZYDiamondTools practical guide on how to effectively dress diamond wheels for optimal performance.

- Surface Roughness5 – Wikipedia page describing surface roughness parameters like Ra and their measurement.

- Flash Rust6 – Van Air Systems article explaining what flash rust is and strategies to prevent it on metal surfaces.